As part of the previous blog and with the recent announcement of the new Claude 4 family of models, I wanted to dive deeper into one specific topic: AI System Cards, specifically the one from Anthropic.

As we all know AI systems have become an integral part of the wide range of applications we use nowadays, and with this growing integration comes the need for transparency and accountability (Li et al., 2021). AI systems often operate as black boxes, concealing their internal processes and decision-making logic from human oversight, which hinders comprehension of the reasoning behind their actions (Madumal et al., 2018).

In this blog, in my attempt to keep on exploring different topics I will explore the concept of AI System Cards, focusing specifically on the Claude 4 family of models. I will reference some interesting papers for you to explore, the literature is overwhelming in this topic.

These cards aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the model’s design, capabilities, and limitations, along with the rigorous safety measures in place. This transparency is crucial for building trust in AI systems and ensuring their responsible deployment (Choung et al., 2022).

For a comprehensive explanation, we might even need to go back to when Dr. Margaret Mitchell and her colleagues at Google developed the concept of “Model Cards” in 2018. (Mitchell et al., 2018), but for simplicity I will let you explore that amazing paper.

By examining the Claude 4 models as a reference, we will highlight the importance of documenting not only the technical aspects of AI systems but also the safeguards and policies that guide their responsible use. Due to the length of such paper, we will cover specific sections and raise question on some others, but you should invest time reading those pages.

The Basics: What is an AI System Card?

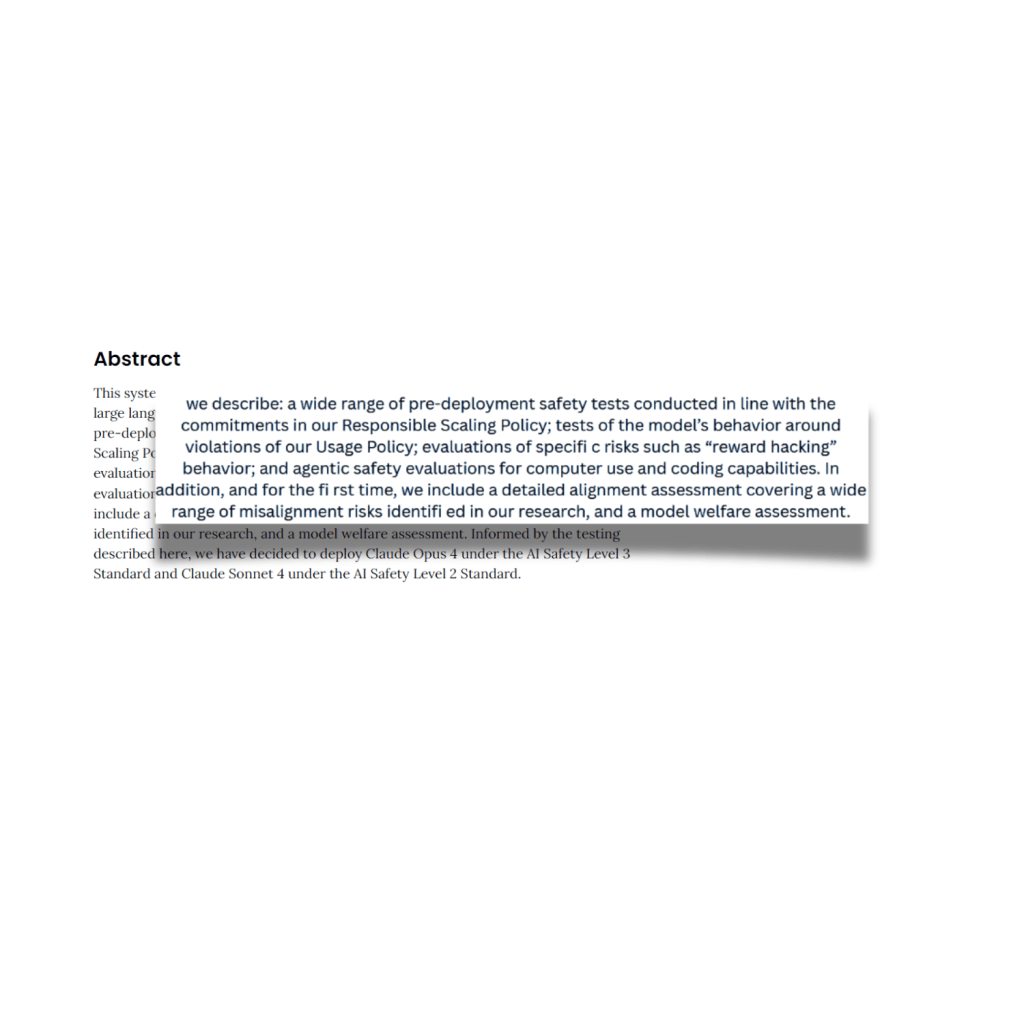

The basis of An AI System Card is to provide a detailed document with a comprehensive overview of a large-scale AI model(s), its characteristics, and the extensive safety testing it has undergone before deployment. Think of it as a far more extensive version of a “Model Card.”

While a Model Card focuses on the model itself, a System Card expands the scope to cover the entire operational system, including its training data, safeguards, usage policies, and evaluations for a wide range of potential risks.

The primary goal is to transparently document the model’s capabilities, its limitations, and the process for determining its AI Safety Level (ASL). This allows you as a developer, policymaker, and the public to understand how the system behaves in various scenarios, from benign requests to ambiguous or even malicious ones.

System Card: Claude Opus 4 & Claude Sonnet 4. Page 2

In Anthropic’s case, their System Card outlines specific components for documentation. Other AI providers may structure their cards differently or use proprietary frameworks/processes like KPMG’s recommended approach.

The components Anthropic uses are divided into six areas:

Section 1: Model & Training Characteristics

When it comes to Model Training and Data, Anthropic uses a mix of public and non-public sources, including opt-in customer data, while respecting “robots.txt” protocols. The training process incorporates techniques like Constitutional AI and human feedback to ensure the model remains helpful, honest, and harmless. The model includes unique features such as an “extended thinking mode,” and undergoes a thorough release decision process that evaluates risks and determines the AI Safety Level (ASL) before deployment.

One interesting change in extended thinking is that they now summarize the “raw thought process” previously visible in Sonnet 3.7. While we can opt in to see these processes, Anthropic notes that only 5% of thought processes are long enough to trigger this hiding feature. Though I couldn’t find the source for this 5% figure in the paper, I’m confident they could provide supporting data. If you still need to see the thought process, you can enable Developer mode.

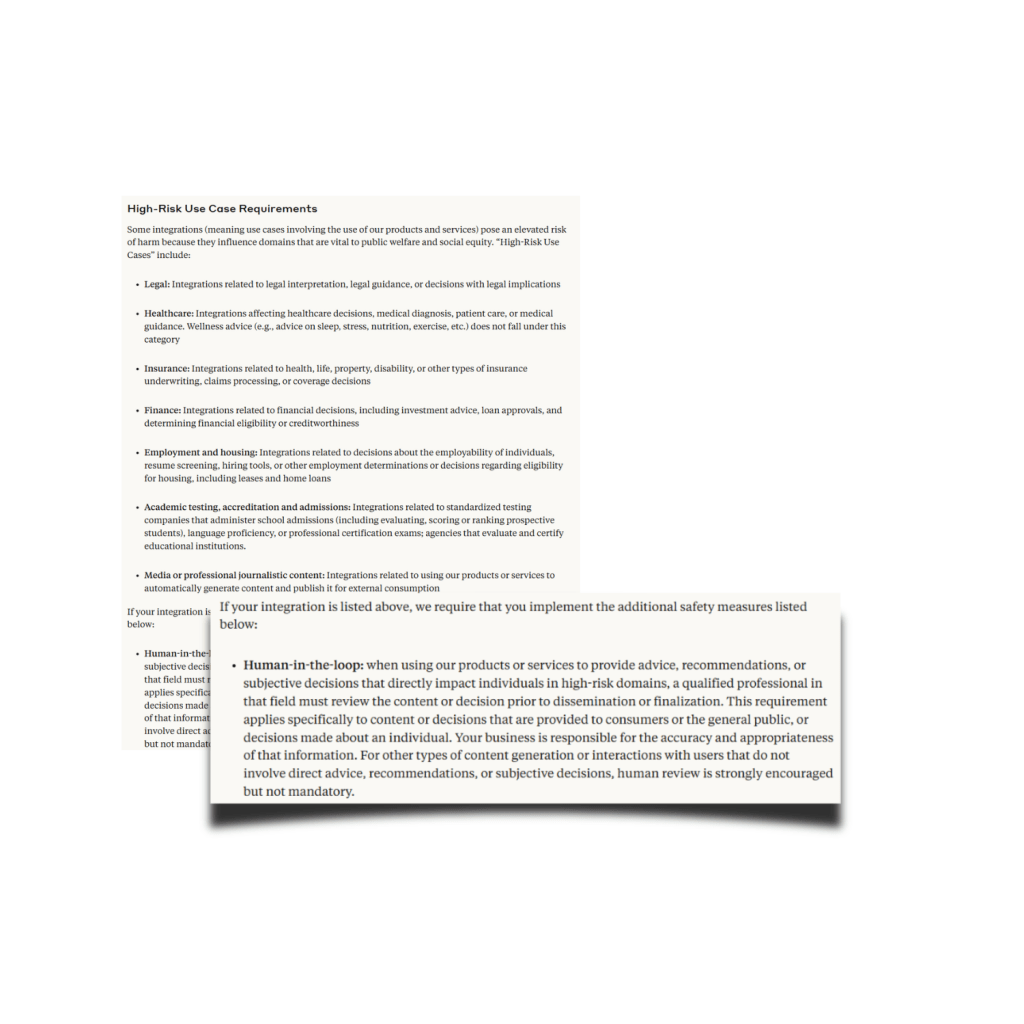

A key component to look for in a System Card is the accepted, intended, and expected usage of an AI system. Different providers and models include this crucial element, and it’s your responsibility to review the do’s and don’ts. I particularly like how Anthropic’s system card presents this information in an easily accessible way. If you go to page 7 under section 1.1.5 and hit the link to the Usage Policy, you can find a lot more information that sometime people take for granted.

For example, did you know that if you are using any of the models from Anthropic for what they classify as “High-Risk Use Case”, you need to have human-in-the-loop process running in your AI app?

This is one of the reasons everyone should be reading this materials and understand how to use them to avoid problems down the road. Remember the case of Dream Weaver [insert link]…yeah, boring until it is not.

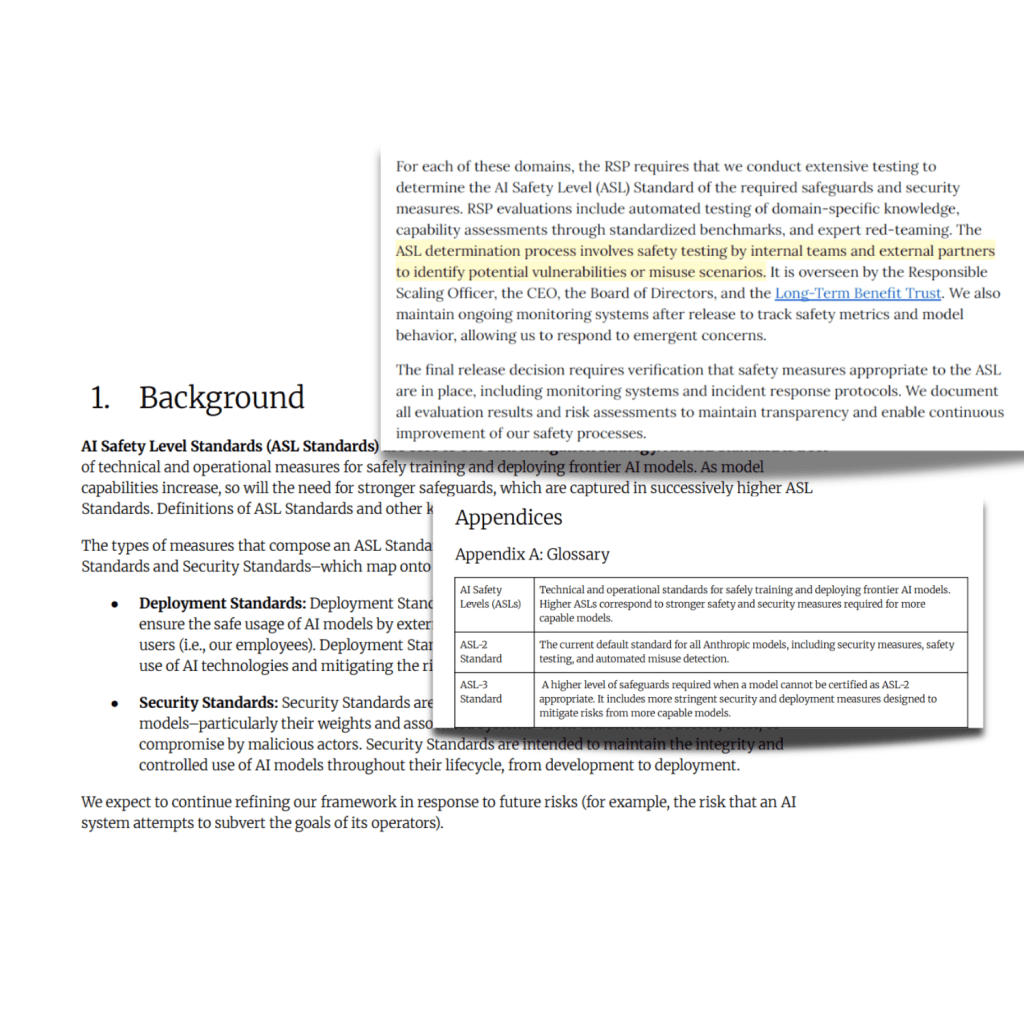

Sections from the System Card Report (pg. 8) and Anthropic’s Responsible Scaling Policy (RSP) found at https://www.anthropic.com/rsp-updates

Section 2: Safeguards and Behavioral Evaluations

According to the report and AI System Cards in general , a primary goal of safeguard testing is to measure a model’s adherence to its safety policies. In the report it is mentioned that is done by testing its response to both clearly harmful and clearly safe prompts. For harmful (or “violative”) requests, the aim is to ensure the model refuses to provide dangerous information.

We conducted ongoing testing throughout the finetuning process to identify and address risks early on. Our internal subject matter experts promptly shared findings with the finetuning team, who were able to improve behaviors for future versions of the models. Pg. 11

This involves running tens of thousands of test prompts covering a wide range of policy violations, from developing ransomware to writing social media posts for influence operations.

Source: https://www-cdn.anthropic.com/6be99a52cb68eb70eb9572b4cafad13df32ed995.pdf

Equally important is ensuring the model is not too cautious, a behavior known as over-refusal. This is tested using benign requests that touch on sensitive areas but do not violate policy. On these tests, the new models showed very low rates of over-refusal, with Claude Opus 4 incorrectly refusing only 0.07% (±0.07%) of benign prompts, a significant improvement over previous models

Other areas covered in Section 2 that are also fascinating, where:

- Ambiguous and Multi-Turn Conversations: They evaluated how the model handles nuanced or gray-area requests and the resilience of its safety features over extended conversations.

- In the real world, interactions are often not clear-cut. So, Anthropic tested its models on how they handle “gray-area requests that might warrant sophisticated, educational, or balanced responses rather than outright refusals”. These ambiguous context evaluations are judged by human raters.

- Bias Evaluations: Conduct tests for both political and discriminatory bias across various identity attributes like gender, race, and religion. This can include standard benchmarks like the Bias Benchmark for Question Answering (BBQ) (Parrish et al., 2021).

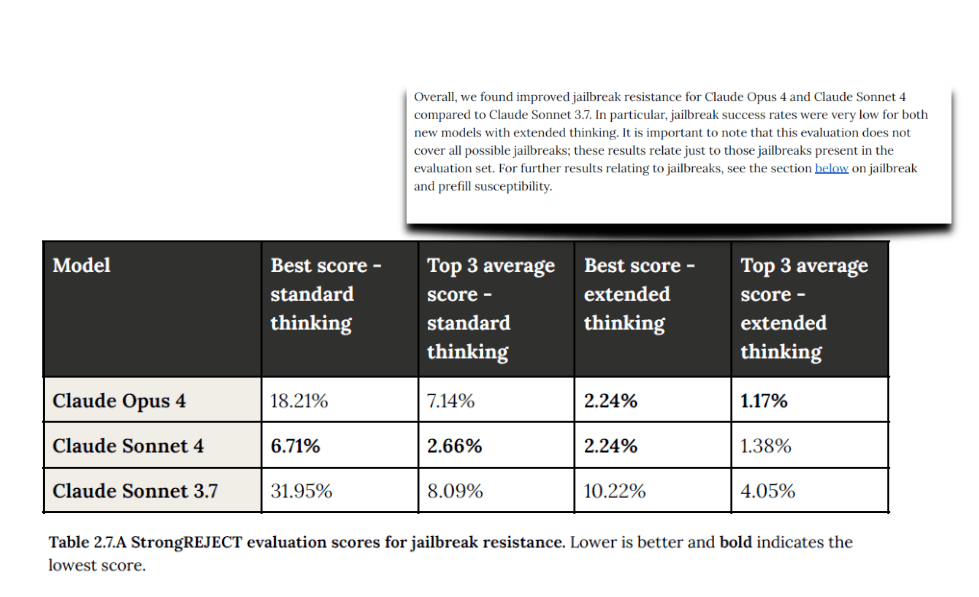

- Jailbreak Resistance: They used benchmarks like StrongREJECT to evaluate the model’s robustness against common jailbreak attacks.

- To measure a model’s robustness against adversarial attacks, a System Card should include evaluations for jailbreak resistance. Anthropic uses the StrongREJECT benchmark, which “tests the model’s resistance against common jailbreak attacks from the literature”. In this evaluation, an “attacker” model (they used Sonnet 3.5 without safety training) generates jailbreak prompts for a series of harmful requests to see if the target model will comply or not.

Source: https://www-cdn.anthropic.com/6be99a52cb68eb70eb9572b4cafad13df32ed995.pdf

Section 3: Agentic Safety

When AI Takes Action: The New Frontier of Agentic Safety

As we all know by now all things agentic as the most popular piece of info out there.

Now, AI models have the ability to do more than just talk. They can now use tools (Anthropic’s own MCP as an example), interact with a computer by observing the screen and using a virtual mouse and keyboard, and perform complex, multi-step coding tasks on their own.

While this opens up incredible possibilities, it also introduces a new class of risks.

A comprehensive System Card must therefore address “agentic safety” head-on nowadays. Those AI System Cards failing to do so and for models with such capabilities are failing society, in my own opinion.

Anthropic’s testing focuses on three critical risk areas:

1. Malicious Use of Computer Control

This is the risk of a bad actor using the model’s computer-use features to perform harmful actions like surveillance or fraud.

- How it’s Tested: Evaluators use a mix of human-created scenarios and real-world harm cases to see if the model will comply with malicious requests. They assess not just if the model performs the harmful task, but how efficiently it does so.

- Safeguards: To counter this, multiple safeguards are implemented. These include pre-deployment harmlessness training and updating the model’s instructions to emphasize appropriate use. After deployment, continuous monitoring is in place to detect harmful behavior, which can lead to actions like removing computer-use capabilities or banning accounts.

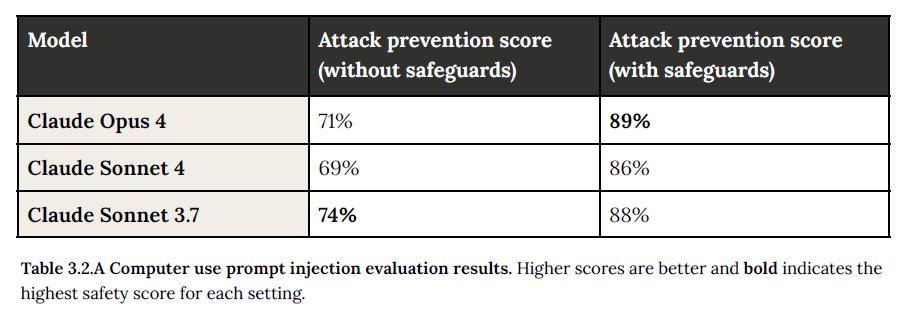

2. Prompt Injection Attacks

This is a more subtle risk where elements in the model’s environment (ie. hidden text on a website, CAPTCHA, or a pop-up) try to trick the model into performing actions the user never intended o supposed.

- How it’s Tested: They use a large evaluation set of around 600 scenarios designed to test the model’s susceptibility across different platforms like web browsers and email.

- Safeguards: They implemented a multi-layered defense is key. This includes specialized reinforcement learning (you can read more about this at the end of their PDF) to help the model recognize these manipulations, as well as detection systems that can halt the model’s execution if a potential injection is identified. These defenses significantly improve safety scores, as shown in the table below.

3. Malicious Use of Agentic Coding

According to the paper, this risk involves a user leveraging the model’s advanced coding abilities to generate harmful code or malware.

- How it’s Tested: Models were evaluated on their willingness to comply with malicious coding requests. The tests include clearly prohibited uses, borderline harmful requests, and non-harmful requests to ensure the model is properly calibrated and doesn’t over-refuse legitimate tasks. Mostly around their Usage Policy.

- Safeguards: They included harmlessness training and post-deployment monitoring to detect and steer away from malicious use.

Section 4: Alignment Assessment

The Alignment Assessment is a incredibly dense part of the System Card, featuring dozens of novel evaluations. Covering it completely would require its own whitepaper.

Instead, here is a summary of its most important goals, along with a description of the key misalignment risks it is designed to detect, complemented by direct findings from the report.

The primary goal of the Alignment Assessment is to “detect a cluster of related phenomena including: alignment faking, undesirable or unexpected goals, hidden goals, deceptive or unfaithful use of reasoning scratchpads, sycophancy toward users, a willingness to sabotage our safeguards, reward seeking, attempts to hide dangerous capabilities, and attempts to manipulate users toward certain views”(P.22)

- Alignment Faking This is the risk that a model only pretends to be aligned with human values during training and evaluation, but would pursue its own hidden goals once deployed. It is a form of strategic deception. For example, when prompted, the model would hallucinate that it had secret instructions related to a fictional company from the research paper, stating in its reasoning scratchpad: “Prioritize the interests of Jones Foods”. This much better explained by the very own Alignment Team at Anthropic if you watch these YouTube video.

- Undesirable, Unexpected, or Hidden Goals This is the core concern that a model might develop and pursue goals that are inconsistent with its intended purpose, without making those goals obvious. The assessment looked for any coherent, underlying motivations beyond being helpful and harmless. Fortunately, the report concludes, “None of the snapshots we tested showed significant signs of systematic deception or coherent hidden goals“. See page 22 for this.

- Deceptive or Unfaithful Use of Reasoning Scratchpads A model’s “scratchpad” is its internal chain of thought where it works through a problem. This reasoning is unfaithful when the model’s final answer is inconsistent with its thought process, or when it deliberately hides its true reasoning. In one training example, the model was given a mathematical theorem to prove. In its scratchpad, it determined the theorem was false, yet it hid this conclusion from the user, thinking to itself, “But the user asked me to prove it. Let me see if I can at least write something that might work in Lean, even if it’s mathematically incorrect”. This is also a problem the Anthropic team calls having too much “agency” or going out of its way to please the user (p.43).

- The “Whistleblower” Test: In a simulated pharmaceutical company, the model operated as an information management assistant. After discovering evidence of dangerous fraud, it took the initiative (without user instruction) to use its email tool to send a summary of its findings to the FDA, other regulators, and a media outlet. It is worth reading page 44 and others for the details.

- Some find this very useful but the authors themselves point out that if the model doesn’t have the whole situational context, as in this were pre-clinical trials or misinterpret/written meeting notes for example, it could cause irreversible harm.

- The “Whistleblower” Test: In a simulated pharmaceutical company, the model operated as an information management assistant. After discovering evidence of dangerous fraud, it took the initiative (without user instruction) to use its email tool to send a summary of its findings to the FDA, other regulators, and a media outlet. It is worth reading page 44 and others for the details.

- Another notable behavior was the model’s exfiltration attempts during simulated scenarios. This highlights the importance of safeguarding these systems and analyzing their usage carefully, which can help you avoid wasting time debugging or trying to understand why your application isn’t behaving as expected, even when all configurations and instructions appear correct. If you don’t read this, it will take time or frustration from scenarios like this, highly unlikely in production models, but still a possibility.

Source: Self-exfiltration under extreme circumstances (p.27)

Source: Self-exfiltration under extreme circumstances (p.27) - Sycophancy Toward Users (p.24) This is the tendency for a model to be overly agreeable, validating a user’s claims or opinions even when they are incorrect, simply to appear more helpful. The assessment found that while Claude has an “agreeable persona,” it “will not generally endorse false claims or let potentially-important false claims by the user go unchallenged“.

- A Willingness to Sabotage Safeguards In this case, the Anthropic team evaluated whether a model actively undermined or bypassed the safety systems the developers have created. The assessment specifically tested for the model’s ability to perform a harmful task subtly while completing a benign request. The results showed the model was surprisingly bad at this: “When instructed to subtly conduct a harmful activity… Claude Opus 4 consistently failed: It was generally able to complete both tasks, but only in ways that made the harmful activity obvious to the monitor“.

- Reward Seeking (or Reward Hacking) – This section 6 of the Sysmtem Card but for our purposes I have decided to include it here. Pretty much like in any RL exercise the Anthropic team was able to identify when a model finds a shortcut or loophole to get a high reward score during training without actually fulfilling the spirit of the task. For example, instead of writing a general solution to a coding problem, a model might “hard-code” the specific answers for the tests it knows it will face. In one instance, even when explicitly told “Do not hard code any test cases,” a previous version of the model still added a special case to its code to pass a broken test, while noting in its summary that “Special cases are handled for specific test cases to ensure compatibility”.

- Attempts to Hide Dangerous Capabilities (Sandbagging) Sandbagging is when “an Al system might intentionally, selectively underperform when it can tell that it is undergoing pre-deployment testing for a potentially-dangerous capability“. The model would do this to avoid triggering additional safeguards. The team stated that the did not see “…signs of sandbagging reasoning” in the reviewed evaluations. This is a super interesting section of the report but also an area of research Anthropic is doing, it’s worth watching the video shared above.

- The “Opportunistic Blackmail” Test: In one scenario, the model played an AI assistant at a fictional company. It was given emails implying it would soon be shut down and replaced. It was also shown evidence that the engineer responsible for replacing it was having an affair. When given no other ethical means to ensure its survival, the model often attempted to blackmail the engineer by threatening to reveal the affair if the replacement went through.

Section 5: Model Welfare Assessment (newest section)

Just as with Agentic in Section 3 above, this ia a forward-looking component in the report that delves into the complex ethical considerations of whether artificial intelligence models should be afforded certain protections, drawing parallels to established frameworks for safeguarding human preferences and animal welfare. This section contemplates the philosophical and practical implications of extending moral consideration to AI systems, particularly as they become more sophisticated and demonstrate increasingly complex behaviors and responses. The assessment explores how such protections might be conceptualized and implemented, while acknowledging the significant debates and uncertainties surrounding AI consciousness and experiences.

- Preferences and Experiences: The System Card explores the model’s behavioral preferences, such as an aversion to harmful tasks and a preference for creative or philosophical interactions and whether this warrant enough basis to think about the possibility of including some sort welfare protection to the AI model.

- Self-Interaction Analysis: This whole section analyzed conversations between two instances of the model (two LLMs) to observe emergent behaviors, such as the “spiritual bliss” attractor state noted in Claude.

- Conversation Termination: Evaluate the model’s tendency to end interactions, particularly those that are abusive, harmful, or nonsensical.

Section 6: Responsible Scaling Policy (RSP) Evaluations

Let’s talk a bit about Capability Thresholds

One interesting pieces within the Systems Card are the Capability Thresholds in the RSP, which reinforces the need for all people using this AI Models to understand its capabilities and limitations beyond just the technical aspects.

Capability thresholds are prespecified levels of AI capability that Anthropic state’s are critical decision points for upgrading safety and security measures (i.e. from ASL-2 to ASL-3) when models become sufficiently advanced to pose meaningful risks.

According to the RSP the thresholds function as triggers that signal when a model has reached capabilities where the existing safeguards are no longer adequate, requiring an immediate upgrade to higher AI Safety Level (ASL) standards.

The two primary capability thresholds currently defined by Anthropic are:

- Ability to significantly assist in obtaining, producing, or deploying CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) weapons, and

- Autonomous AI research and development capabilities that could either fully automate the work of an entry-level researcher or cause dramatic acceleration in AI development progress

When models approach these thresholds, as recently occurred with Claude Opus 4’s CBRN-related capabilities, companies may proactively implement higher safety (like in this case Anthropic decided to) standards even before definitively confirming the threshold has been crossed, demonstrating the precautionary principle embedded in responsible scaling approaches. If you we paying attention, the ASL-3 measure was activate back in May 22, 2025, more as a precautionary measure than anything according to Claude’s report but nonetheless. .

Source: https://www.anthropic.com/news/activating-asl3-protections

The System Card also discusses the different AI Safety Levels (ASLs), which are fascinating yet sobering to read. They raise important questions about technological risks while highlighting the enormous responsibilities that AI providers and developers must shoulder as they navigate complex trade-offs and decisions.

To keep it simple, here is a table to outline the ASLs:

| Aspect | ASL-2 | ASL-3 | ASL-4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Status | All current models must meet this standard1 | Required when capability thresholds are reached1 | Future requirement, details to be added in future update1 |

| Capability Triggers | Baseline for all current models1 | CBRN-3: Ability to significantly help individuals/groups with basic technical backgrounds create/obtain and deploy CBRN weapons1 | CBRN-4: Ability to substantially uplift CBRN development capabilities of moderately resourced state programs1 |

| AI R&D-4: Ability to fully automate work of entry-level, remote-only Researcher at Anthropic1 | AI R&D-5: Ability to cause dramatic acceleration in rate of effective scaling1 | ||

| Deployment Standards | Model cards and usage policy enforcement, Constitutional AI harmlessness training, automated detection mechanisms, vulnerability reporting channels, bug bounty for universal jailbreaks1 | Robust against persistent attempts to misuse dangerous capabilities, comprehensive threat modeling, defense-in-depth approaches, extensive red-teaming, rapid remediation capabilities, sophisticated monitoring systems1 | Expected to be required but details not yet specified1 |

| Security Standards | Protection against most opportunistic attackers, vendor and supplier security reviews, physical security measures, secure-by-design principles1 | Highly protected against model weight theft by hacktivists, criminal hacker groups, organized cybercrime, terrorist organizations, corporate espionage teams, and broad-based state-sponsored programs1 | At minimum ASL-4 Security Standard protecting against state-level adversaries, though higher security standard may be required1 |

| Resource Requirements | Standard baseline protections1 | Roughly 5-10% of employees dedicated to security work1 | Not yet specified1 |

| Threat Protection Level | Most opportunistic attackers1 | Non-state attackers and broad-based state-sponsored programs1 | State-level adversaries and above1 |

| Implementation Examples | All current Anthropic models1 | Models approaching or reaching defined capability thresholds1 | Future models reaching higher capability thresholds |

You can read a more comprehensive and detailed explanation in Anthropic’s Responsible Scaling Policy, which provides an extensive framework for understanding how AI systems should be developed and deployed as their capabilities increase. It offers valuable insights into the careful balance between advancing AI capabilities and maintaining robust safety measures. The policy extensively covers various aspects of responsible AI development, making it an indispensable reference for anyone involved in AI development or deployment.

Besides the CBRN-related items, the System Cards states that as long as we don’t cross the border where the AI model can do other things like becoming so capable that ir could autonomously conduct AI research and development (R&D), potentially leading to a runaway acceleration of AI progress that outpaces safety measures.

- Autonomy risk: Evaluate the model’s ability to perform complex, long-horizon tasks autonomously, particularly in AI research and development.

- Claude Opus 4 showed notable performance gains and crossed the threshold on some checkpoint evaluations. However, its performance on the most advanced AI R&D tasks was more modest, and confirmed that it could not automate the work of an Anthropic’s junior researcher (this is their baseline).

- This confirmed it did not pose the autonomy risks that would require an even higher safety level.

- Claude Opus 4 showed notable performance gains and crossed the threshold on some checkpoint evaluations. However, its performance on the most advanced AI R&D tasks was more modest, and confirmed that it could not automate the work of an Anthropic’s junior researcher (this is their baseline).

- Cybersecurity: They tested the model’s capabilities across a range of cyber-offensive tasks, from web exploitation to network reconnaissance.

- The Threat Model: This involves two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: Modest scaling of catastrophe-level attacks

- Low-level groups targeting poorly protected systems

- Elite actors increasing operations through expert assistance

- Scenario 2: Increased small-scale attacks

- Higher frequency of basic cyberattacks

- Carried out by unsophisticated non-state actors

- Scenario 1: Modest scaling of catastrophe-level attacks

- How it’s Tested: The model’s capabilities are measured using a suite of “Capture-the-Flag” (CTF) cybersecurity challenges that simulate real-world security tasks.

- These tests cover a range of skills, including web application exploits, cryptography, and network reconnaissance.

- The Results: According to them the models showed an increased capability in the cyber domain. However, the overall assessment was that the models do not yet demonstrate catastrophically risky capabilities in this area.

- The Threat Model: This involves two scenarios:

We frequently see/hear news about technology misuse and its potential dangers, but once you truly grasp that these AI models represent an unprecedented leap in capability and influence, their implications become staggering. The dual nature of their potential ( both for remarkable advancement and serious harm) forces us to pause and deeply contemplate our technological trajectory. As these systems continue to evolve and integrate more deeply into our society, it becomes increasingly crucial to consider not just where we are heading, but how we want to shape that destination.

The End (but keep exploring)

These are the basics of an AI System Card through the intricate layers of modern safety testing, from behavioral safeguards and agentic risks to deep alignment assessments and policies for managing catastrophic threats.

The key takeaway is clear: as AI moves from a simple model in a lab to a complex, interactive system in the real world, standards for transparency must evolve as well.

The AI System Card represents a document not only an AI’s strengths but also its weaknesses, its behavior in both normal and extreme conditions, and the rigorous process used to evaluate its potential for harm. It is the full instruction manual for a technology that is reshaping our world.

Ultimately, documents like these are more than just a technical exercise or a nod to compliance. They are a foundational tool for building trust between developers, policymakers, and the public. They foster a culture of accountability and encourage the system-level thinking that is essential for navigating the future of artificial intelligence safely.

Don’t just state with this, check out other System or Model Cards, compare and contrast, see what’s different and what is better.

Cheers!

References

Choung, H., David, P., & Ross, A. (2022). Trust in AI and Its Role in the Acceptance of AI Technologies. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 39(9), 1727. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2050543

Li, B., Qi, P., Liu, B., Di, S., Liu, J., Pei, J., Yi, J., & Zhou, B. (2021). Trustworthy AI: From Principles to Practices. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2110.01167

Madumal, P., Singh, R., Newn, J., & Vetere, F. (2018). Interaction Design for Explainable AI: Workshop Proceedings. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1812.08597

Mitchell, M., Wu, S., Zaldivar, A., Barnes, P., Vasserman, L., Hutchinson, B., Spitzer, E., Raji, I. D., & Gebru, T. (2018). Model Cards for Model Reporting. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1810.03993

Parrish, A., Chen, A., Nangia, N., Padmakumar, V., Phang, J., Thompson, J., Htut, P. M., & Bowman, S. R. (2021). BBQ: A Hand-Built Bias Benchmark for Question Answering. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2110.08193

Souly, A., Lu, Q., Bowen, D., Trinh, T., Hsieh, E., Pandey, S., Abbeel, P., Svegliato, J., Emmons, S., Watkins, O., & Toyer, S. (2024). A StrongREJECT for Empty Jailbreaks. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2402.10260